Changing Climate in Southwest Florida

Learn more about how a changing climate is influencing SWFL

For examples of studies and resources supporting the information presented below, please check out our climate library.

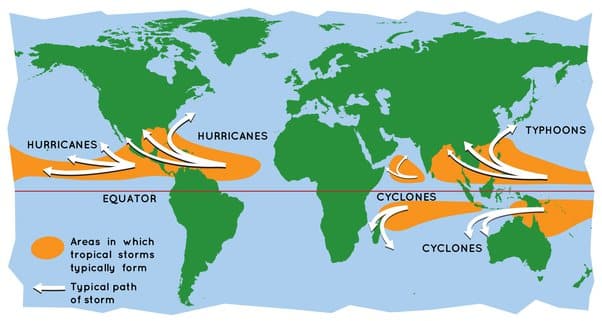

Hurricanes are a natural phenomenon that most Floridians are well-acquainted with. These storms form near the equator where they are fueled by warm ocean waters at temperatures of 80° Fahrenheit or above.

Areas where tropical cyclones tend to form. Tropical cyclones that form in the North Atlantic and the central or eastern North Pacific are alternatively called hurricanes, while those in the Northwest Pacific are called typhoons. Image credit: NASA Space Place

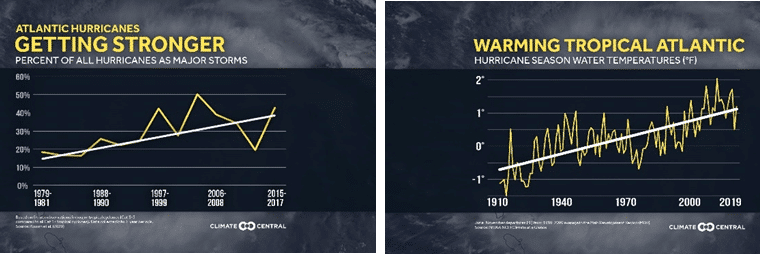

However, the nature of hurricanes has been shifting under the influence of climate change. Rising average sea surface temperatures have caused the proportion of more intense hurricanes – those at Category 3 or above – to creep up over time.

Image credits: Climate Central

Recent studies highlight other potential changes to hurricane behavior. Storms appear to travel more slowly on average than in past decades due to a possible slowing of the winds that drive them forward. And, they may be taking longer to weaken once over land as they retain more moisture, or “fuel,” from warm seas. The likelihood of a hurricane to rapidly intensify – which refers to an increase in wind speed of 35 miles per hour or more within 24 hours – appears to be increasing, giving people less time to respond and ensure their safety.

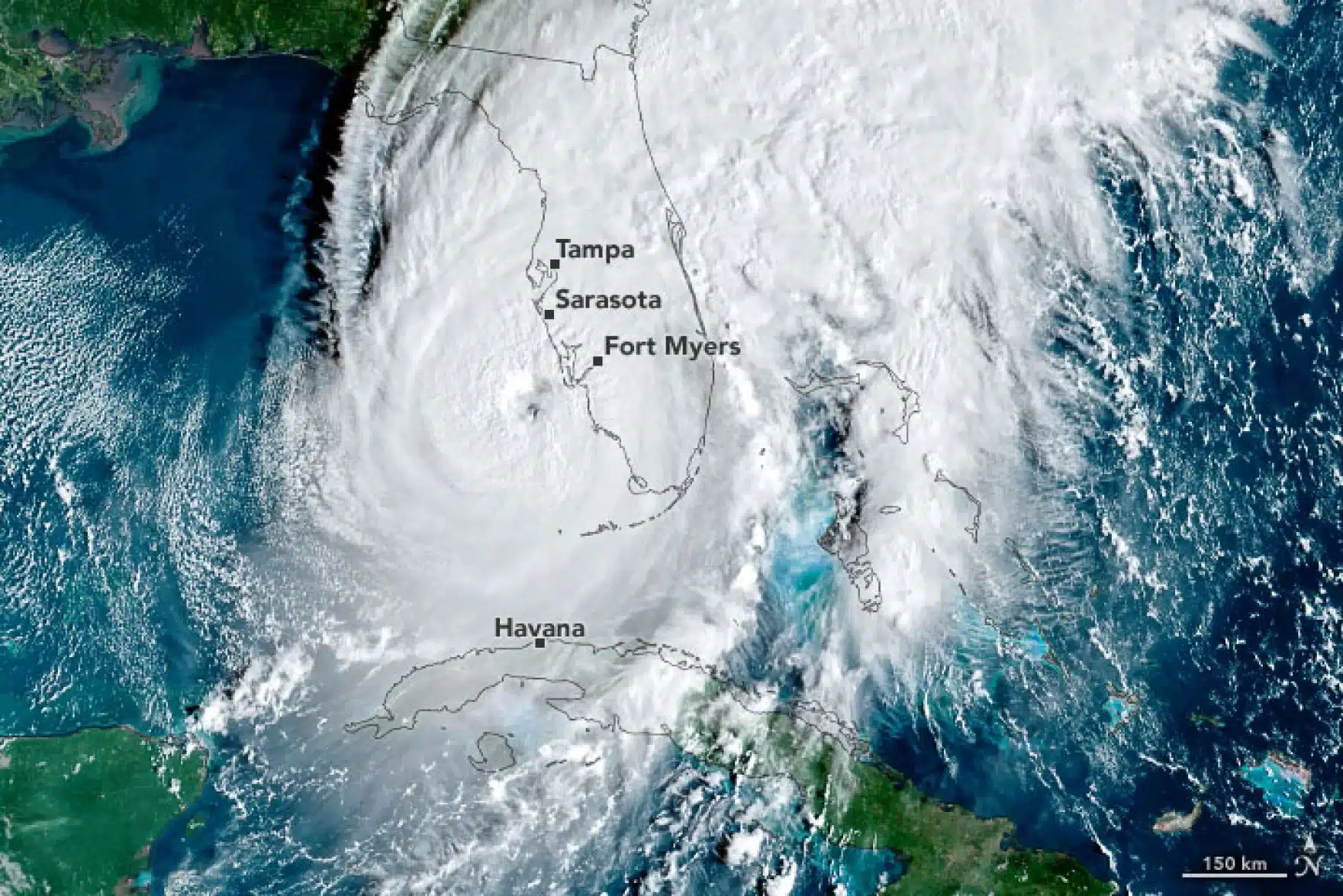

Scientists don’t point to single storms as being caused solely by climate change, instead examining its influence on hurricane characteristics over time. However, Hurricane Ian which significantly impacted Southwest Florida in September of 2022, has many of the hallmarks of these trends.

Hurricane Ian over Florida on September 28, 2022. Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Ian ambled its way across Florida at an average speed of 8-9 miles per hour (as compared to 2004’s Hurricane Charley which traveled a very similar path across the state at speeds between 15-25 miles per hour). Ian also went through at least two periods of rapid intensification over the course of its lifetime. Scientists estimated that Hurricane Ian produced 10% more rain because of the influence of climate change. All these factors led to record levels of storm surge and flooding in the region.

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.

Many Florida communities, both inland and coastal, have been noticing heightened flooding from multiple sources. Climate modeling also suggests many of these may increase in magnitude over time.

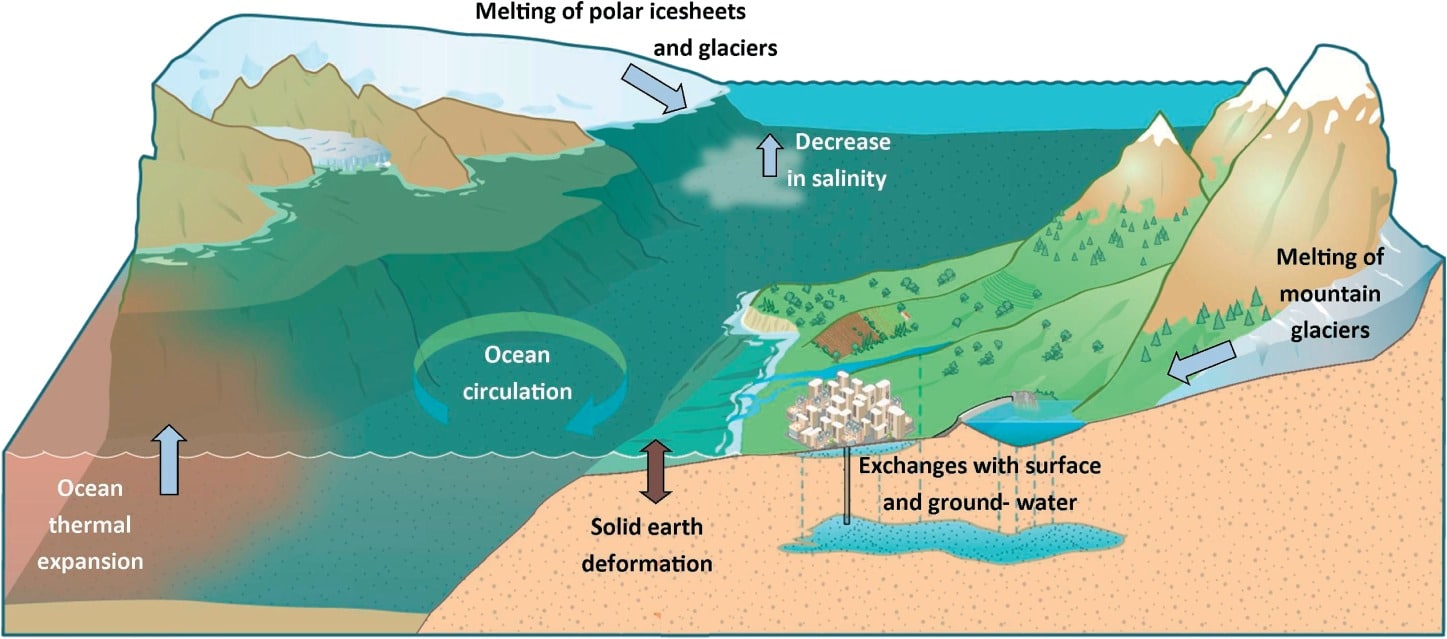

Sea Level Rise

Globally, increases in sea levels are primarily due to two influences. The first is “thermal expansion,” which refers to the tendency of water molecules to move farther apart from each other when warmed up. This has been happening especially in the top layer of the ocean as sea surface temperatures rise. The second is the addition of water when land-locked ice, like glaciers, melts. Additional factors – like how water circulates around coastlines or if land is rising or sinking over time – can contribute to local rates of sea level rise that differ from larger regional and global patterns.

Image Credit: Cazenave and Cozannet, 2013

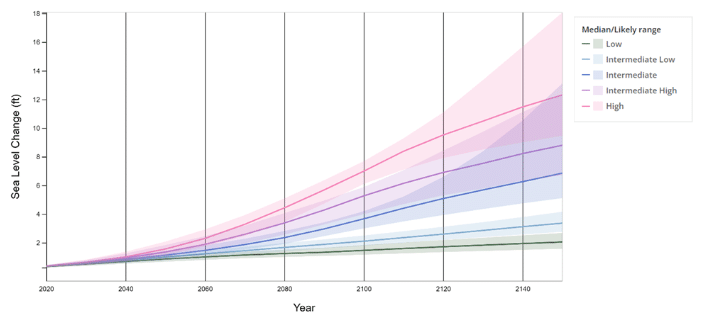

To see what’s predicted for our area in the future, we can look at projections for sea level rise based on data from local NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) tide gauges. Here’s a figure based on the gauge for Naples:

Image Credit: Interagency Sea Level Rise Scenario Tool

You may notice that there are multiple lines on the graph indicating possibilities for how sea level might behave over time. You can think of these as a series of “possible futures.” These futures take into account sources of uncertainty. The first source is scientific uncertainty around how certain influences like melting glaciers may unfold over time. The second takes into account how future emission rates of greenhouse gases, which are linked to the warming that contributes to rising seas, may change in response to human behavior. In all of these scenarios, you’ll notice the lines become more curved and less straight over time, suggesting faster rates of sea level rise in the future.

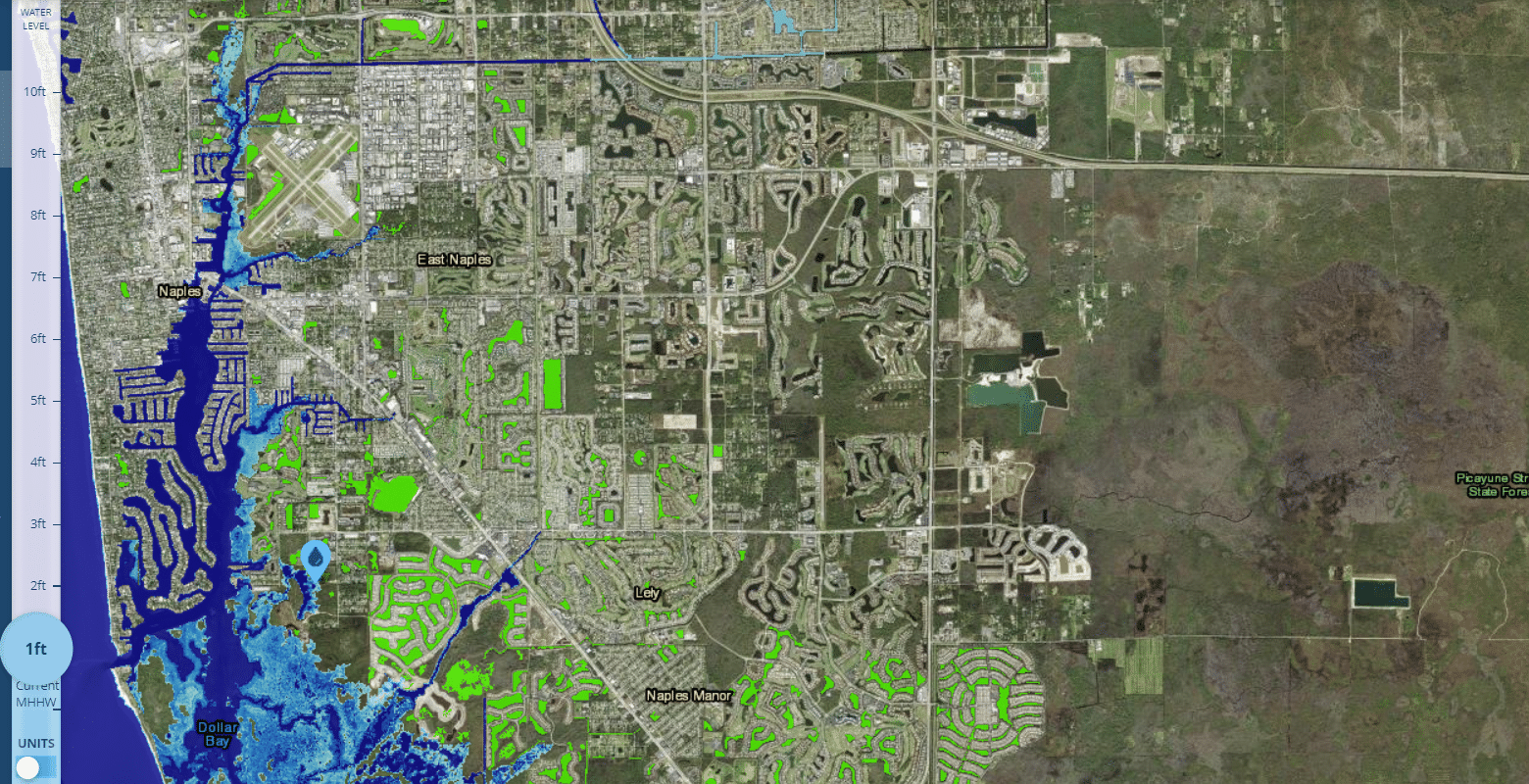

Because Florida is very flat, even minimal flooding can have outsized impacts. The NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer simulates the flooding that can occur based on different depths of sea level rise. The following shows current conditions in a portion of the Naples area, and illustrates where you can expect water during mean higher high water (MHHW) – the highest high tides of the day:

The following image shows new areas that will start to be inundated during the highest high tides of the day with the addition of 1 foot of sea level rise. (Green areas represented low-lying locations that are not connected to bodies of water but could still potentially flood). According to the series of possible futures shown earlier, we might expect this to occur somewhere between roughly 2040 and 2060:

Other Sources of Flooding

Sea level rise is not the only process contributing to current and future flooding in the State. The increase in more intense and slower hurricanes that are more likely to rapidly intensify translates into more potential exposure to high levels of storm surge. Heavy rain events are also becoming more frequent and dropping more water in a single event. Rising seas can cause water tables to rise and worsen groundwater flooding.

Many of the communities working on adapting to flooding are considering solutions that address some or all of these sources as well as instances of compound flooding, where more than one type of flooding happens at the same time.

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.

High Heat Days

In recent years, a lot of attention has been focused on flooding issues within the state, but high heat days are equally important (and are a key cause of increased flooding). Starting in 2023, the globe has been experiencing an especially sustained amount of record-breaking heat for more than a year affecting both air, land, and ocean. This has implications for humans and our natural environment.

For instance, we have a significant number of outdoor workers – contractors, landscapers, farmers and farmhands, environmental professionals, etc. – that are exposed to conditions that can result in heat-related illness. Older and younger community members, especially those without adequate access to air conditioning, are also at elevated risk.

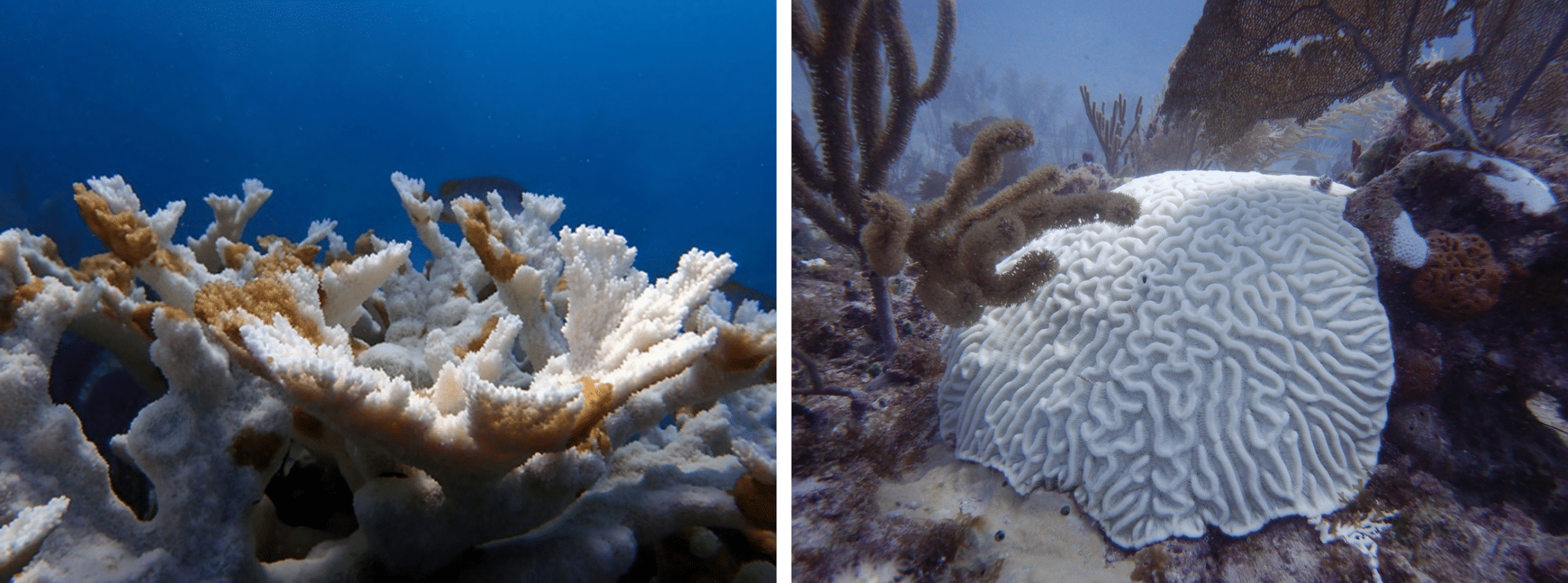

Our corals in particular have been a key example of how heat stress can affect ocean life and other wildlife. During the summer of 2023, many corals around the Florida Keys expelled their zooxanthellae – tiny photosynthetic organisms that live inside the corals’ bodies benefitting from protection while providing helpful nutrients. We call these expulsion events “coral bleaching.” Protected species elkhorn and staghorn coral were particularly impacted. Visit this FWC page to see how the prevalence of bleaching events has increased over time.

Bleached Corals. Image Credits: Coral Restoration Foundation, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

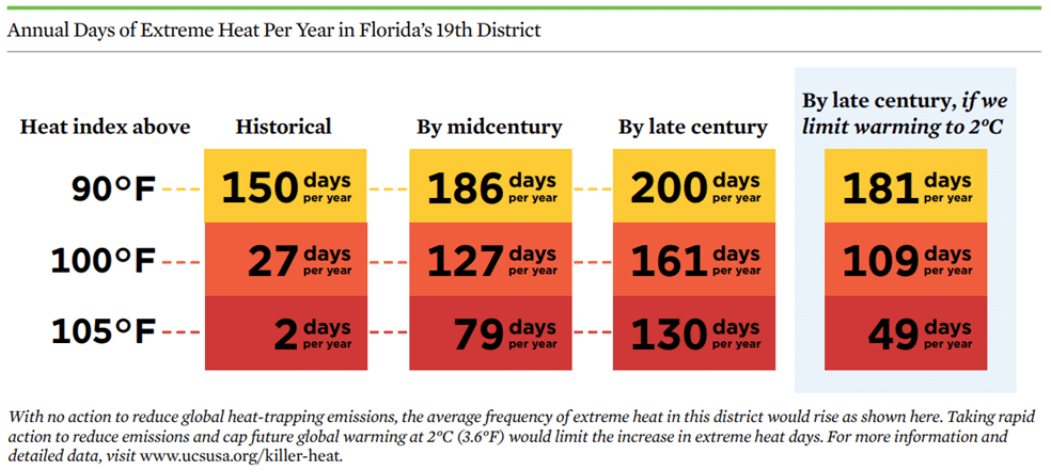

A tool developed by the Union of Concerned Scientists shows predictions for high heat index days for different areas. Heat index refers to how hot a day actually “feels” to us, based on a combination of factors like temperature and humidity. The following are predictions for Florida’s 19th Congressional District which contains portions of Lee and Collier Counties. You can read more about ways to address heat on our climate page.

Image Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.

The health of our local waters is intimately connected to our changing climate in multiple ways. Gases do not dissolve as readily into warmer waters. This can translate into lower amounts of available dissolved oxygen which makes it harder for aquatic wildlife to breathe.

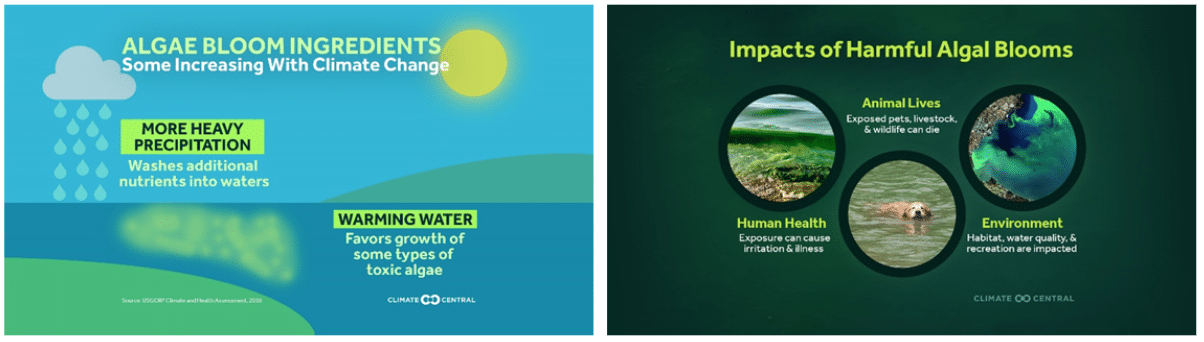

The increase in events that bring heavy rain can introduce more stormwater runoff along with extra nutrients into water bodies that often are already experiencing degraded water quality. More nutrients paired with warmer water act as fuel that can combine with other factors to amplify, or change the persistence or timing of, naturally occurring periods of rapid growth (“blooms”) of macroalgae (seaweed) like Sargassum or smaller free-living species of phytoplankton (microscopic plant-like organisms that drift with water currents). When these naturally occurring blooms experience overgrowth that causes significant negative impacts to their surroundings, we often call them “harmful algal blooms” (HABs).

Image Credits: Climate Central

When there’s too much algae in a system and it can’t all be eaten by its natural grazers, it often dies and then may be broken down by bacteria that use up oxygen. This is another pathway leading to low dissolved oxygen in surrounding waters.

Under the right conditions, some species of algae can also produce toxins. In freshwater, this is often associated with types of blue-green algae. In the local coastal waters of SWFL, toxins from a type of phyto-plankton called Karenia brevis is responsible for the airborne respiratory irritation and other symptoms associated with red tide in our region. These and other algal toxins can have severe consequences for both wildlife and humans.

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.

Rising seas can introduce saltwater into areas that had predominately been exposed to freshwater. Multiple sources of flooding can introduce lots of water into habitats that used to be mostly dry. The plants and animals in these situations need to find ways to adapt or will be replaced by others that are better able to tolerate the new conditions. Some of our important local coastal habitats like mangrove forest and oyster reefs can, under the right conditions, increase their elevation and keep up with some sea level rise. But, in other instances, they will migrate inland to places with more favorable conditions. Less hard freezes have also resulted in mangroves expanding their range further north in Florida, sometimes overtaking the salt marshes that were there before.

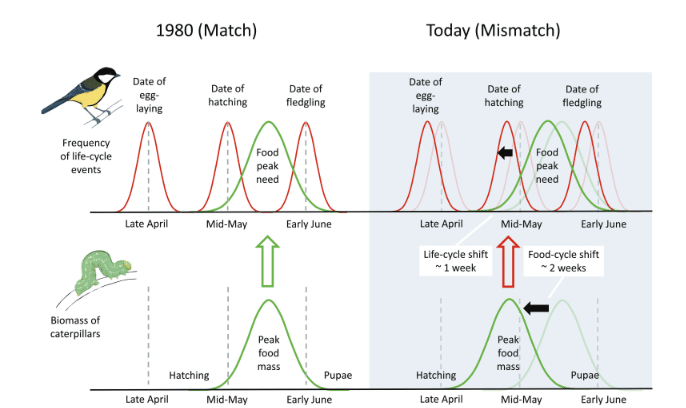

Earlier arrival of warm temperatures has started to shift parts of some organism’s biological cycles to earlier in the year. For instance, the Conservancy’s von Arx Wildlife Hospital has been recording earlier admission of baby birds than when the hospital was first established. This can become a problem for wildlife if these changes create a mismatch in the timing of when a resource they need – perhaps a food source – is available.

Example of mismatch that has been documented (Visser et al., various studies) between the hatching of great tit chicks in the Netherlands and the availability of the caterpillars they eat. Image Credit: Barbara Mizumo Tomotani, 2017

Heat can also have some less expected influences on wildlife. For some animals like sea turtles, nest temperature will determine if hatchlings are male or female. Incubation temperatures above 88 °F result in females, and temperatures below 81 °F mean males. A nest experiencing temperatures between that range will produce a mix of males and females. But as temperatures have been rising, more female sea turtles have been born, and there are a lot fewer male sea turtles to go around as mates. Researchers are still exploring the implications, but reduced genetic diversity and health of sea turtle populations could be an effect.

Example of news headlines in recent years around the prevalence of female sea turtles being born in Florida.

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.

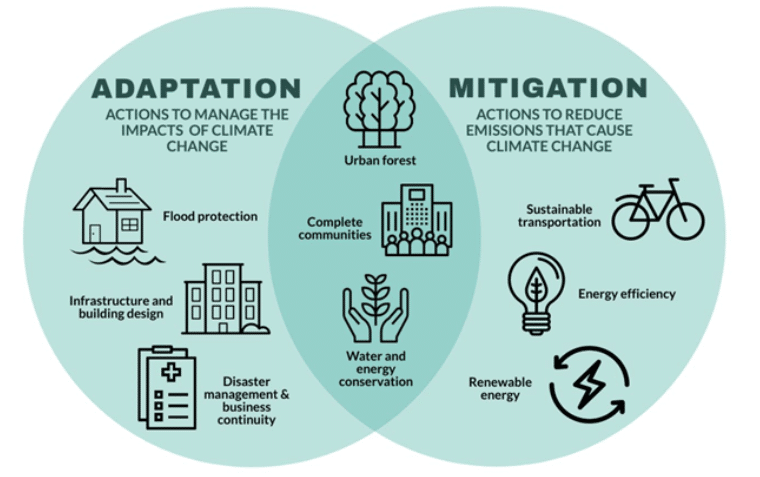

At the broadest level, there are two categories of potential responses to a changing climate: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation focuses on reducing the severity of future climate impacts, largely by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Regardless of how effective we are at mitigating these emissions in the future, we will not stop all increased warming. This is because there is a lag in the warming that results from emissions that have already been released. So, we are locked into some degree of impacts like hot days and rising seas. Adaptation refers to finding strategies that help us co-exist with or protect ourselves from these impacts. But the two are intimately connected. If we mitigate greenhouse gases and can reduce the severity of future conditions, we can more successfully adapt.

Examples of Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies. Some strategies fall under both categories. Image credit: ICLEI Canada, 2019

Strategies for Mitigation

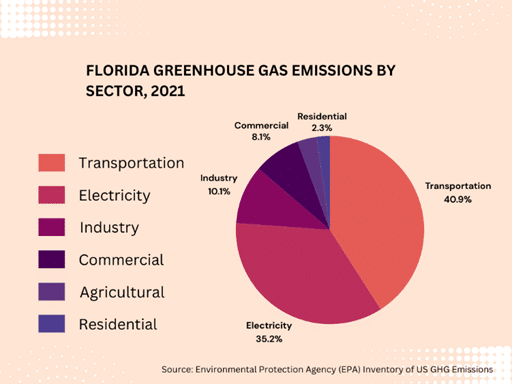

Mitigation can happen across many different sectors that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and at different scales. For instance, data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) shows that for Florida, most emissions come from transportation and electricity generation. This means there is significant opportunity to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) across these sectors by improving both energy efficiency and the availability of renewable energy to support how we get our power and how we get around. This can happen at the Federal and State level by planning and regulating entities.

But, there’s also a lot you can do in your daily life! The following are some examples of various actions you can adopt as they make sense for you:

- Wash clothes and dishes with cold water when possible.

- Compare different modes of travel when you take trips to see which produce less emissions.

- Opt to switch some of your events to virtual attendance.

- Try and switch to reusable products rather than single-use options including plastics when possible. Emissions from plastic production are poised to become a leading GHG source in the future.

- Look into whether renewable energy options like solar panels or an electric vehicle might be right for you. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes some associated incentives you might be able to take advantage of.

- Look into improving your home’s energy efficiency (efficient appliances, insulating your home), and being mindful of your energy use. This can also translate into saving money!

Strategies for Adaptation

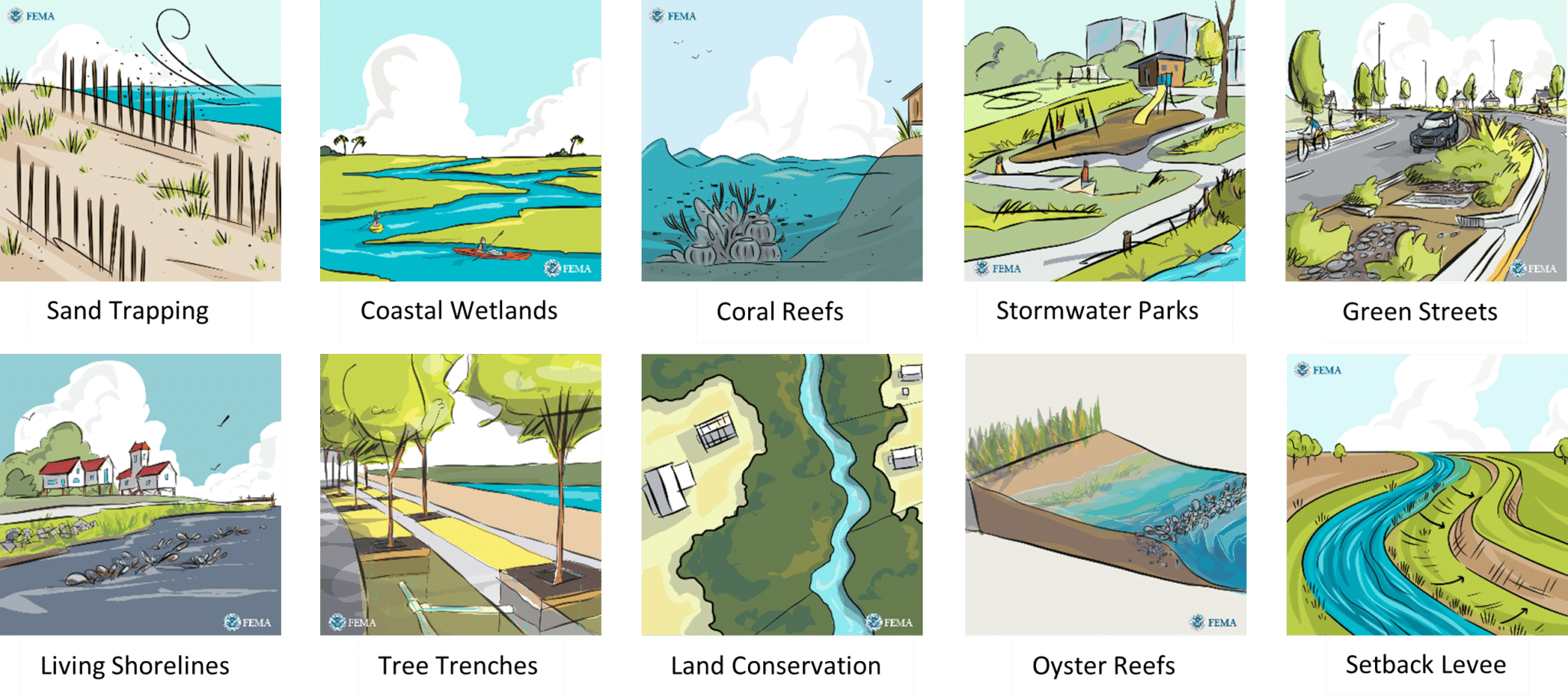

Adaptation options can take many different forms and purposes. For instance, public policy, education campaigns, and building code changes are all possible solutions that build resilience in different ways to climate change. However, some adaptation strategies rely on physical structures or elements put in place to help protect communities from these stressors. While this can sometimes take the form of hardened (often called “grey”) infrastructure like sea walls or flood gates that can result in significant environmental impact, the Conservancy especially advocates for working with nature and capitalizing on the protective advantages it provides us.

Terms like nature-based solutions and green infrastructure are commonly used to refer to strategies that leverage the protective benefits of nature. Nature-based solutions include using pre-existing natural systems or options constructed using living or natural elements to solve issues related to flooding, heat, degraded water quality, etc. Habitats like mangrove forest and beach dunes can help reduce incoming wind and wave energy while marshes can also provide extra water storage. Living shorelines can be constructed out of components like mangroves, marsh grasses, and oyster reefs to help provide shoreline protection. Establishing expansive tree canopy can provide shelter for people from blazing temperatures and reduce the amount of stormwater reaching the ground.

Examples of types of nature-based solutions. Image credit: FEMA

These nature-based solutions often provide a whole range of benefits as compared to the narrow function of grey infrastructure. This includes services like providing habitat, improving water quality, and even sopping up carbon which often means they can be considered a solution for adaptation and mitigation. They sometimes also cost less to conserve, restore, construct, or maintain which provides more return on investment to the communities that implement them.

For a downloadable fact sheet of this content, click here.